In fact, there is a recent incident where Trump (or his people) decided to distract from a real issue with a much more dramatic and interesting issue, now that I have gotten thinking about it. For example, have you heard about this?

Vice President-elect Mike Pence went to Hamilton and the cast included an impromptu speech to him, outraging Trump.

Now look at the dates in that article. The showing that Pence went to was on November 18th. Do you know what also happened on November 18th?

Trump settled the fraud lawsuit over his “Trump University” for $25 Million dollars.

It just kinda stands out that these happened at the same time, and that I hear people talking about the first one a lot but I don’t really hear about the second one very much.

Robert Reich is the Secretary of Labor in the Clinton administration and a Professor of Public Policy at the University of California. Here on his blog, he posted about how Donald Trump controls the media. Trump, to me, seems like the nightmare the “spectacle” as Debord defines it created.

Watch this video for an explanation of why you shouldn’t buy into the spectacle of gendered products.

Visual rhetoric refers not only to the visual object as a communicative artifact but also to a perspective scholars take on visual or visual data. In this meaning of the term, visual rhetoric constitutes a theoretical perspective that involves the analysis of the symbolic or communicative aspects of visual artifacts.

Sonja K. Foss, Framing the Study of Visual Rhetoric: Toward a Transformation of Rhetorical Theory, pages 305-306

Debord observed that the spectacle actively alters human interactions and relationships. Images influence our lives and beliefs on a daily basis; advertising manufactures new desires and aspirations. The media interprets (and reduces) the world for us with the use of simple narratives. Photography and film collapses time and geographic distance — providing the illusion of universal connectivity.

An Illustrated Guide to Guy Debord’s ‘The Society of the Spectacle’

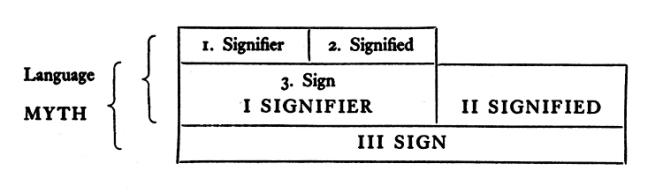

It can be seen that in myth there are two semiological systems, one of which is staggered in relation to the other: a linguistic system, 114 the language (or the modes of representation which are assimilated to it), which I shall call the language-object, because it is the language which myth gets hold of in order to build its own system; and myth itself, which I shall call metalanguage, because it is a second language, in which one speaks about the first. When he reflects on a metalanguage, the semiologist no longer needs to ask himself questions about the composition of the languageobject, he no longer has to take into account the details of the linguistic schema; he will only need to know its total term, or global sign, and only inasmuch as this term lends itself to myth. This is why the semiologist is entitled to treat in the same way writing and pictures: what he retains from them is the fact that they are both signs, that they both reach the threshold of myth endowed with the same signifying function, that they constitute, one just as much as the other, a language-object.

Roland Barthes, Mythologies, page 114

The spectacle takes on many more forms today than it did during Debord’s lifetime. It can be found on every screen that you look at. It is the advertisements plastered on the subway and the pop-up ads that appear in your browser. It is the listicle telling you “10 things you need to know about ‘x.’” The spectacle reduces reality to an endless supply of commodifiable fragments, while encouraging us to focus on appearances.

An Illustrated Guide to Guy Debord’s ‘The Society of the Spectacle’